MotM Reunion | Meet Baye: Two Years Later

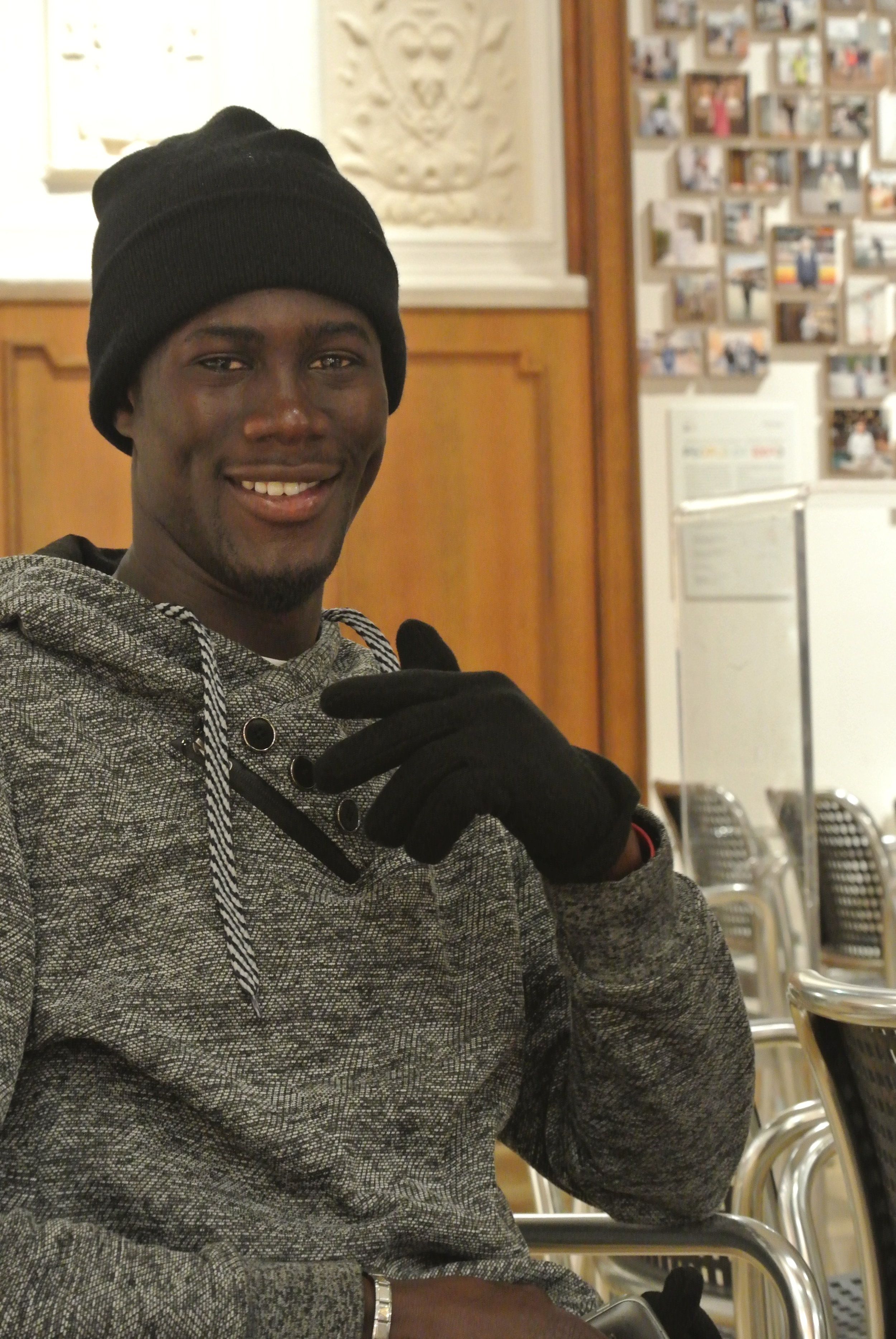

Baye in Milan, Italy. June 9, 2018. © 2018 Pamela Kerpius

19 September 2018

MotM Reunion

Meet Baye: Two Years Later

The reckoning comes in the next first meeting.

Imagine the only way you know someone up until that point is how they appeared on Lampedusa. Maybe they were a little gray in the eyes. Maybe, they were still in a state of shock. Always, they were in suits of donated, mis-matched clothing that may not have even matched the season. Puffy jackets in May. Thin t-shirts in November.

Imagine, the last time you saw them they were wearing shoes that didn’t fit, or possibly, flip-flops in winter, or worse––if shoes were out of stock––a pair of bedroom slippers, which they’d use through the mud and rain.

This is not an image of dignity, much less of strength.

So there is a reckoning in your encounter with a person later when they are alive in the mix of a thriving city that doesn’t accommodate a trauma narrative like Lampedusa. You realize right away that the things that happened to migrants in the Sahara, in Libya, even back home before they left, and of course out there on the open sea, will always be with them, but it is not who they are.

Their journey is not their identity. It is instead, something to understand about them, an element that shaped, but did not determine their character.

This might sound self-evident, but how easy it is have this obscured in the moment when you are hearing the gritty details of what happened. Like everything in Lampedusa, things get trapped there. It can be hard to telegraph to the beyond.

But then, for people like Baye (21, Senegal) who I met in Lampedusa in November 2016, that was an exterior he was shedding right away, with ferocity. Sometimes people I meet make it clear, verbally, that these shabby clothes, this dependency on shared state housing, even at first reception; this dependency on the tasteless food they are provided and must eat out of necessity, is not really them.

Baye moved with swiftness. He made clear he was a person meant to get out there, work and succeed, and it was a bit trite to deliberate upon that any further. Let’s go, was always the direction of his tone.

So it was zero surprise when I met him for the first time in Milan, where he lives now, in April 2017, striding across the piazza with the confidence of a native. He navigated the streets with speed. He told me about work. At the time, on- and off-loading crates from a truck at a nearby market. He didn’t mind the job, but did mind being paid a mere twenty euros for 8 hours or more of labor.

Baye was not the only migrant I knew to recognize his labor was being exploited, but he was among the first to state it with clear authority. It was a complaint waged in real hopes that maybe voicing it could change it. He is not one to keep things bottled up. He is not one to mince words. Baye is a guy who shows up, looks the part––whether at work or walking through the streets––and expects better.

He was starting school, Italian classes from volunteer teachers, in April 2017, and already spoke pretty well. He switched to Italian in our conversation, and his skill had already eclipsed my own.

When we met again in central Milan six months later in November 2017, it was just past his one-year anniversary. He was late, and I chalked it up to what my East African friends who work as cultural mediators at the housing centers call “Africa time,” but I’ve spent enough time in central and southern Italy to know this might just as well be “Italy time.” So, you know, cultural synchronicity and that.

The holidays were approaching and the streets were sparkling. He took us on a tour of the center of the city. He said he knew where to go to find the food he likes, although it was expensive for him to buy with the tiny cash subsidy he got from the state every month. But he knew where to get it. He knew the lay of the land, the metro, the streets, the pace of the crowds on the sidewalk. He knew where to find his friends too.

“I only have Black friends,” he said then. Integration was mostly imaginary. When we met again, for our third visit together in Milan, in June 2018, I met his friends. They are all migrants. He took me to the corners of the park where his crews would hang. Some came through Lampedusa too.

He looked different this time though, exhausted and out of words. He kept pace, but his eyes were drained. He had a cold, he was fasting all day from Ramadan, and he had just completed a shift at a construction site in spite of the impediments to his energy. I worried about him working at such an intense pitch without food or water. These jobs though, they come and go and are not reliable. If he let this one pass, who knows when another might come.

Next month, in late October 2018, is his asylum hearing. It has finally been set, Baye informed me then in June. That is the real reckoning. But I think he will be ready. His Italian is good now, and he’s been studying English and general curriculum too.

He was particular about how I took his photo on the park bench that early evening. He wanted to look strong in spite of the sickness, in spite of the long day of work and fasting. The sunlight filtered through the trees like magic. He looked up, I snapped and walked back to the bench to show him the outcome and he approved. It was a picture of what he knew he was all along, even when a place like Lampedusa would not let him show it.

Baye is an amazing human being.

Read Baye's original journey story, recorded November 2016 >